Last summer, four organizations came together to launch a new program in 17 St. Louis Public elementary schools. The Institute for School Partnership (ISP), The Little Bit Foundation (TLBF), and St. Louis Public Schools (SLPS), with funding from the Bayer Fund, developed a pilot program to increase capacity for STEM teaching and learning in SLPS. The program is designed to remove barriers for teachers and provide access to high-quality, hands-on STEM education for St. Louis City students.

The pilot program, grounded in the most current research on science learning, provides SLPS students with inquiry-based STEM curriculum and materials through the mySci program and makerspace kits. It engages educators in innovative professional development focused on supporting students of all backgrounds and abilities to participate fully in activities that lead to healthy understanding of grade-level science and engineering concepts.

“Struggle is an essential part of learning and instead of avoiding challenges we decided to embrace them. We let go of the idea that the pilot would look the same as it would have pre-pandemic.”

Rachel Ruggirello

For a moment, the accelerating pandemic looked like it might sideline the pilot. “This was not the ideal situation in which to initiate this ambitious program,” said Rachel Ruggirello, ISP associate director and ISP lead on the pilot program. “But struggle is an essential part of learning and instead of avoiding challenges we decided to embrace them. We let go of the idea that the pilot would look the same as it would have pre-pandemic.”

Ruggirello is pleased they moved forward. She said as it turned out, this was exactly the year to offer a fresh initiative and support teachers as they leaned into a new kind of teaching.

Building the foundation

Bringing together the ISP, SLPS and TLBF to develop, manage and implement the program required building foundational relationships and logistical processes. The partnership involves leveraging the combined strengths of each partner to achieve a level of impact not accomplished independently. This co-creation approach ensures that the program is relevant to all partners.

Ruggirello worked with Maura Cosgrove, STEM program coordinator for TLBF, Carrie Launius, SLPS elementary science coordinator and SLPS lead on the program, Glenn Barnes, K-12 social studies coordinator for SLPS, and Emily Gentemann, fourth-grade teacher at Dewey International Studies Elementary School, and a teacher leader on the project.

“A great synergy developed quickly between the partners. We realized that collectively we have the power to do great work in the district.”

Carrie Launius

“A great synergy developed quickly between the partners,” Launius explained. “We realized that collectively we have the power to do great work in the district. We have laid a strong foundation for this program to provide a brighter path for SLPS students.”

Ruggirello added that the partners are investing the time, people, and resources necessary to forge an effective, long-range program. There is mutual respect, trust, and discourse in the team and a shared commitment to high-quality STEM teaching and learning in SLPS.

Eighty-five educators took part in the pilot program — that figure includes teachers, district administrators and academic instructional coaches. Over 1,200 students in 60 classrooms received STEM resources as part of the pilot.

“This was a hard year, but it was a year of incredible resilience for teachers and students. It was a year of innovation and creativity that emerged in spite of the pandemic,” Barnes said. “They say necessity is the mother of invention and this partnership helped us leverage the crisis to teach more science than ever before and better science than ever before.”

Hooked on science

Many schools started the year remotely before eventually shifting to in-person instruction. Despite the fluidity of the situation, Lisa Abernathy, fourth and fifth grade science teacher at Mann Elementary said the timing of the pilot was perfect.

“I absolutely love the mySci program,” she said. “Every lesson has something that gets kids engaged and active and working with each other. It gets them to think critically. It got the students excited about learning. Especially this year, they needed something to be interesting and exciting.”

Laura Watson, a third, fourth and fifth grade science teacher at Meramec Elementary loves that mySci uses an active learning approach to teaching science. “It sparks the students’ curiosity, it’s student-friendly and has enrichment activities if students want to dive deeper into the content,” she said.

Gentemann said on most days, she felt like a magician trying trick after trick to keep her pandemic fatigued students engaged. “I can’t keep pulling rabbits out of my hat to keep them excited. With the mySci program, I didn’t have to invent the rabbit.”

Reaching all students

One of the desired outcomes for the pilot program was increasing student participation in the SLPS district science fair, which for years has seen most entries coming from the magnet schools. Launius wanted to change that. She wants the experience to be accessible to all students.

“This year was better than it’s ever been!” she said. “The pilot program was able to change teachers’ mindsets and show them how critical engineering is to support collaborative innovation and problem solving. Even teachers that didn’t participate in the science fair were still able to engage their students in engineering.”

Science fair entries this year included a mask dispenser, sock-assist gadget, cellphone dog mount and even a student sized car.

Students in Annette Rockett’s third-grade class at Columbia Elementary used a shipping pallet and a crate to build the car. It took them three tries to get it assembled.

“They worked on it for months and they were so proud of themselves,” said Amanda Curtis, STEM teacher at Columbia Elementary and the school’s science fair coordinator. “Seeing them test their final project was great. The car whizzing down the hall was so exciting. That learning and success is contagious!”

The car won honorable mention at the science fair. Curtis said that’s a big deal since this was the first time these students participated in the science fair.

Abernathy said taking part in the science fair was a powerful and exciting experience for her students. It allowed all of them to succeed no matter their abilities. “We have kids with different abilities and different languages and the fact they all get to do hands-on science gives them a chance to excel. No textbook memorization means that kids that aren’t super strong in language can still be successful.”

Her sentiment was shared by several teachers who agreed that hands-on learning and not being dependent on a textbook sparked joy in their students.

Launius agreed that the pilot program supported all students. Students who struggle with traditional lessons were able to fully engage in the science and engineering practices. Teachers reported being able to use science as an opportunity to capture students’ imaginations, celebrate student success and build their academic self-esteem.

Exploration

Where do you get your ideas? When did you realize you wanted to be a writer? How long does it take you to write a book?

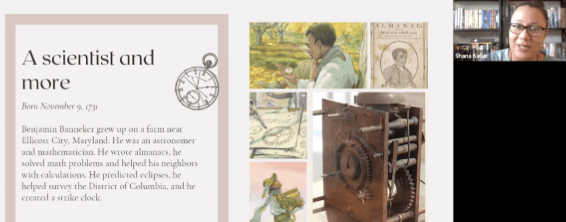

As a way to integrate literature and STEM content, Ruggirello and Launius co-developed an “Ask the Author” series as part of the pilot program. Teachers read books aloud to students prior to virtual, live presentations by the authors. Students came prepared with questions and were enthusiastic contributors to discussion. In all, 15 “Ask the Author” events were held.

“The book talks really hooked me.”

Audrey Hammock

“The book talks really hooked me,” said Audrey Hammock, fourth-grade teacher at Patrick Henry Downtown Academy. “The sessions were fun and something special and interesting.”

She noted that her students really liked the interaction with Tracey Nelson Maurer, author of “Samuel Morse, That’s Who!” Her students were overjoyed when Maurer asked them for feedback on her book.

I could see how proud that made them feel, like they could contribute something, Hammock said. “They were so engaged and then after, they all wanted to make drawings for her as a thank you, for talking to them.”

Children’s literature supports science learning and provides a platform for interdisciplinary exploration. Launius’s expertise in selecting quality STEM books was instrumental in launching this initiative.

“All of the books we selected this year were for a particular purpose,” she explained. “Quality STEM books model real-world innovation, illustrate teamwork, and encourage creativity in support of student inquiry and content knowledge. “

Supporting teachers

Professional development sessions were created by the partnership specifically for this program. The sessions were collaboratively planned and facilitated, with each facilitator contributing their area of expertise. Participating teachers were surveyed to learn what their individual needs were, how they would apply what they were learning and where they wanted to go next.

Teachers and facilitators met virtually for three hours on six Saturday mornings. PD sessions included content focused on the Next Generation Science Standards and Missouri Learning Standards, assessments, tools for teaching virtually, integrating technology, deepening classroom conversations and engineering design and makerspace.

“Often the way teachers learn something is the way they will teach it,” Launius explained. “We know that the best way to learn is to show and not tell, and that’s how we did the PD. We created a new paradigm and mindset shift for teachers. If you start with a small ripple you can have a great impact.”

Teachers engaged in STEM Challenges – monthly activities created by Cosgrove of The Little Bit Foundation – and reflected on how STEM and makerspace activities build students’ capacity to engage in engineering practices and deepen understanding of science content.

“In every session we had work to do as if we were the student and that opened the door to see things differently. It helped us understand their thinking,” Watson said.

“We built aluminum foil boats at a PD session, and a week later I did that in my classroom and the kids loved it,” Abernathy said. “It was a good chance to get excited about teaching science and to build my knowledge so I could bring that back to the kids.”

“This is the best collaboration I have experienced!”

Laura Watson

Watson’s favorite part of the Saturday sessions was talking with the other teachers. She always learned something new – a tip, trick or best practice. “This is the best collaboration I have experienced,” she said. “It helped me to better understand teaching science to students. Before I only had my own lens, now I have the lenses of other educators that also teach across curriculums.”

Rosemary Bruce, academic instructional coach at Columbia Elementary, who has a large role in implementing the new science program said the teachers genuinely embraced the Saturday sessions. “This was the first year that we did content specific professional development in science and I really saw some “ah ha moments” during PD.”

Building out

In spite of the challenges posed by COVID-19, this pilot year was extraordinarily successful in supporting teachers and engaging students in STEM. The Institute for School Partnership, The Little Bit Foundation and Saint Louis Public Schools with the support of the Bayer Fund, seized the moment to shatter assumptions about how and when learning can happen.

The authentic partnership, established by the team’s work on this program, provides a model of collaboration that will be employed to drive positive change in other subject areas. And, as the program matures, the partners envision expanding the work throughout the SLPS district.

Ruggirello said resources and strategic supports are in place for strong, positive growth. As the program moves into the next phase, she is excited about its potential and is confident the district will see continually greater benefits.

She explained, “We’ve built a lot of capacity and will springboard off this foundational year working toward measurable and sustained improvement in SLPS students’ STEM learning.”

Media Contact: Myra López