Located at the southernmost tip of Texas, the Rio Grande Valley is at some points less than a mile from Mexico’s border. While it is home to some of the poorest counties in the country, it’s one of the fastest growing regions in the United States. That growth amounts to more than 340,000 students enrolled a year in K-12 schools, 97% of whom are Latino. All this makes the Rio Grande Valley an unlikely birthplace for an education revolution. Nevertheless, it’s happening, courtesy of a partnership between Washington University in St. Louis and the Texas Graduate Center.

The partnership was born from a 2014 meeting between Margo Hathaway, an accounting and grants specialist with Washington University’s Institute for School Partnership (ISP), and Mary Alice Reyes, the executive director of the Texas Graduate Center (TGC), a nonprofit dedicated to the betterment of public school education in the Valley.

Since 2013, the TGC has partnered with Harvard University to help teachers from the Valley earn a master’s degree from Harvard’s math for teaching graduate program. Reyes was interested in pursuing a similar model at WashU – but with a focus on science.

“We met at a convention, and she inquired about the potential we might have for her nonprofit, whose goal is to increase graduation rates,” explains Hathaway, the program’s coordinator. The goal is for teachers with WashU master’s degrees to be able to provide AP and dual credit courses to their high school students, therefore creating a robust college pipeline. “It’s important for the high school students to enroll in dual credit courses, so they can see themselves moving toward graduation with college credits and even possibly an associate’s degree,” Hathaway says.

“With their advanced degrees, these teachers will fill a critical need for school districts seeking to increase the number of teachers who can teach advanced placement and dual enrollment courses,” Hathaway says. “The Rio Grande Valley has multiple hospitals, and the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley has a medical school. The goal is to be a feeder for that program.”

After much discussion and a few visits, in the summer of 2016, the TGC established its first cohort for WashU’s Master of Science in Biology for Science Teachers program at University College. Ten teachers from five school districts across the Valley joined educators from across the country. The second cohort of four teachers started this past summer.

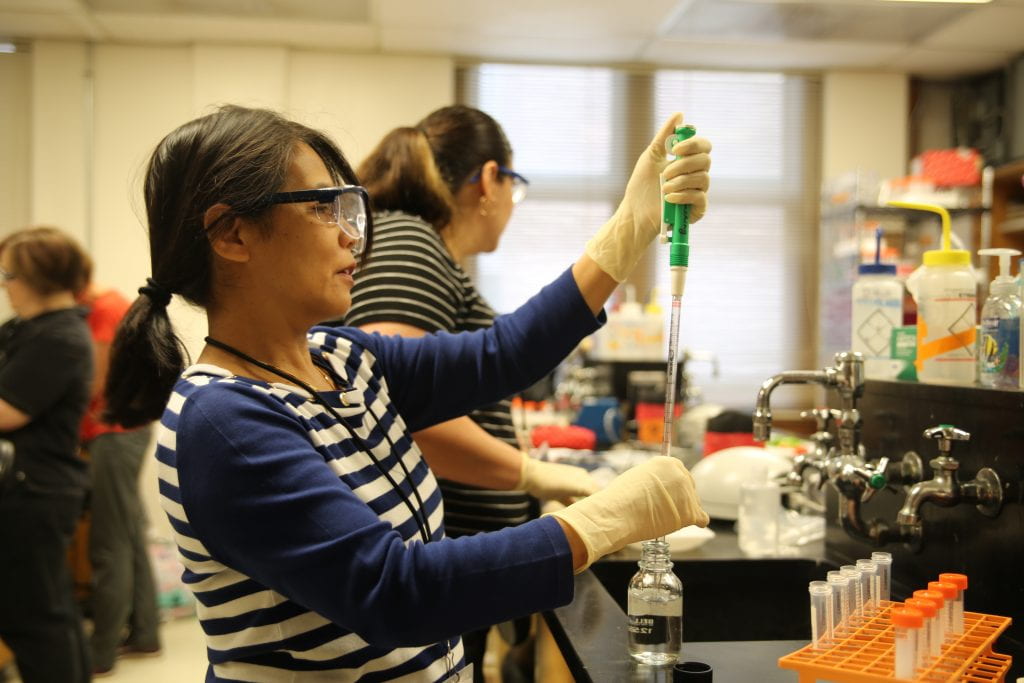

Coordinated by ISP, the two-year program is designed to fit the schedules of working teachers. It consists of two summer institutes, three weeks each, in residence at WashU. The remaining coursework is completed online. The program is funded partly by the school districts and the TGC.

While three weeks is a large chunk of time to be away from work, family, and friends, it affords the cohort a wonderful opportunity to become immersed in the curriculum, labs, and lectures, while bonding with the other participants and their instructors. It’s the magic of the cohort effect.

For many of the Texas participants, especially the women, this opportunity carries a lot of responsibility – not just to better themselves but to uplift their Latino community.

With her shoulder-length black hair, glasses, and youthful air, Iliana Herrera could pass for a high school student. In fact, at 24, she’s only a few years older than her 9th grade biology students at the Academy for Health Science Professions in La Joya, Texas – a school whose emphasis is to prepare future medical leaders.

Herrera has always loved science, and teaching was a great fit. When she found out about the program, applying was a no-brainer. “I am a teacher. We are a family of 11. I don’t have that much money; I am straight out of college. Financially, it’s a gift for me,” she says.

She explains that while a lot of programs aim to make sure you’re a good teacher, WashU’s aims to make sure your knowledge is current. “Especially in science, you cannot afford to not be up-to-date,” she says. “You have to be continuously improving. I tell my kids all the time. ‘I’m not that much older than you, but when I was in school, we had nine planets. Now there are eight.’ In a matter of a couple years, things change.”’

For Herrera, this educational pursuit is packed with emotions. While her parents were very supportive of her higher education goals, she recalled an uncle who essentially said being smart would endanger her marriage prospects. “My goal was to prove him wrong,” she says. “I broke my uncle’s stereotype of what it is to be a female Mexican in the Valley.”

She’s also cognizant of being a role model for her students – especially the ones that live in impoverished border communities known as ‘colonias.’ These neighborhoods have poor infrastructure including a lack of water, electricity, paved roads, streetlights, adequate sewage, wastewater treatment, and trash collection.

“In this political climate where our students are so aware, we need to make sure they are being exposed to good role models,” she says. “I want to show them that it is OK. We can do this. We can break stigmas.”

At 54, Nellie Kvapil, a biology teacher at Mission Collegiate High School in Alton, Texas, was eyeing an early retirement. But after a talk with school leaders, she realized the WashU program was too good to pass up. “It has rearranged all of my plans,” she says with a smile. “At this point in my life, I should be planning for my retirement, but instead I am planning my career goals all over again. This is a win-win situation for me and the school.”

Her last formal college experience was in 1995. She admits being self-conscious about what she describes as “a big knowledge gap.” But she is very impressed with the experts, instructors, speakers, and content. “I feel like I have stepped into the world of giants. It makes me feel so little but, at the same time, so good that I am part of this program,” she says.

Natalia Cantu is the middle child of 11 children, and the first one in her family to further her education past a bachelor’s degree. “I could not say no to this opportunity,” says the 9th grade biology teacher at Johnny G. Economedes High School in Edinburg, Texas. “When are you going to say no to a free education?”

This is Cantu’s third year of teaching, and she feels she has plenty more to learn. Tears fill her eyes as she explains that, while she is terribly homesick, she is motivated to do well in the program by thoughts of her four-year-old daughter. “I want to set an example for her, and leave that stereotypical image that Mexican women have,” she says. “I also have sisters that are in middle and high school, and they are looking to me.”

Single-mother Gloria Garza also draws inspiration from family – specifically her 10-year-old daughter. “I want to show her that she can go wherever she wants. I don’t want her to be limited,” says Garza, a 9th grade biology teacher at Pharr-San Juan-Alamo Early College High School in San Juan, Texas.

Arnulfo Cruz describes himself as a “lifer in the classroom.” He’s entering his 20th year teaching. Currently, he teaches 11th and 12th grade biology at Weslaco East High School in Weslaco, Texas. He’d previously enrolled in a master’s program but lost interest after losing confidence in the program. Over the years, his administrator dropped hints about needing someone with a master’s who could offer certain courses. In 2016, he learned they would have to outsource AP courses to a local community college unless they hired somebody with a master’s. He decided he had nothing to lose and applied.

“I am the father of four girls from 8 to 18, and I want them to see that it’s never too late to better yourself,” he says. “If I can do it, what’s the difference between me and you?” Cruz has a personal stake in making himself a better teacher. “My own kids are my students,” he says. “I have a vested interest.”

At the beginning of each school year, Homer Olivarez asks his science students who among them is interested in a science or STEM career, and it’s rare when a hand goes up. Olivarez, who teaches at Palmview High School in La Joya, Texas, wants to change that indifference.

“I’m pursuing my master’s at WashU so I can start a dual enrollment program back home to teach higher-level biology and get kids motivated,” he says. “I’m trying to start a biology club. I have four kids interested in biology. Ten kids are ready to enroll in dual enrollment. It’s exciting knowing that it might turn into something bigger.”

The first cohort from this TGC partnership will graduate this summer.

For more information on the Master of Science in Biology program for educators, click here.

October 2017 | by, Myra Lopez

Original story published in The Ampersand.