Place-based inquiry is transforming classrooms in this urban elementary school

Patti Pyatt, an experienced fourth grade teacher, eagerly accepted the challenge of teaching at Meramec Elementary, one of the most under-resourced neighborhood schools in the St. Louis Public School District.

“It’s not easy,” she admits. “But we have been learning a lot because our school is part of the innovation zone. I’ve been making some pretty dramatic changes in the way I teach. Honestly, most of our kids in the past have been told rather than taught, in part because discipline was an issue. Keeping kids in their seats and in their textbooks was difficult.”

Perhaps one of the most exciting changes for Pyatt over the past two years is the shift to an Inquiry Block in which science and social studies are taught using place-based pedagogy. Place-based teaching and learning has afforded all sorts of changes that leave her feeling energized and proud of what her students can do.

Place-based teaching and learning has afforded all sorts of changes that leave her feeling energized and proud of what her students can do.

Place-based education (PBE) immerses students in local heritage, cultures, landscapes, opportunities and experiences, using these as a foundation for the study of language arts, mathematics, social studies, science and other subjects across the curriculum.*

Teachers at Meramec began their work with place-based education by reading and discussing The Power of Place, a book that addresses the six design principles of Place-Based Learning:

- Community as Classroom: Communities serve as learning eco-systems for schools, expanding the definition of the classroom.

- Learner-centered: Learning is personally relevant to students and enables agency.

- Inquiry-based: Learning is grounded in observing, asking relevant questions, making predictions, and collecting data.

- Local to global: Local learning serves as a springboard for understanding global issues.

- Design thinking: Learning provides a way for students to make an impact on their communities.

- Interdisciplinary: The curriculum matches the real world and is taught in a real way, frequently through projects. **

The adoption of these principles has brought important changes to the classroom for Pyatt and her students.

“It’s been really amazing to see the shift from my classroom to their classroom,” she says. “They take so much ownership of what is going on. They are always making suggestions for what we should do next. We use the term activator for my role now. I’m helping them make decisions about their learning rather than simply lecturing them. Keeping students in their seats is no longer an issue, because the expectation is students will be up, experimenting, talking to each other, and learning collaboratively.”

“They take so much ownership of what is going on. They are always making suggestions for what we should do next. We use the term activator for my role now. I’m helping them make decisions about their learning rather than simply lecturing them.”

Pyatt says that one of the best parts of this new work has been partnering with the Institute for School Partnership at Washington University in St. Louis (ISP). The Institute provides teachers with well-designed science kits that can form the basis of the place-based inquiry work. These kits provide important foundational materials that allow students to experiment in a hands-on way, rather than reading about a topic in a textbook.

“Now, the kit is not the be all and end all of my science program,” explains Pyatt. “I’m given the time and funding to take that kit to the next level, incorporating place into our study.”

This twist on inquiry has made all the difference.

As Pyatt guides her fourth graders through a unit on sound, the kit helps the class explore learning targets: defining energy (particularly sound energy), model waves, amplitude, wavelength and applying scientific ideas to create a device that makes sound. But Pyatt’s unit does so much more.

As her place-based coach, I studied the unit with her, and we came up with the idea of extending sound study to other countries and cultures. Pyatt ordered five inexpensive instruments from other parts of the world: the Didgeridoo from Australia, the Shofar horn from Israel, the tongue drum from Trinidad, the singing bowl from Thailand, and the goblet drum from West Africa.

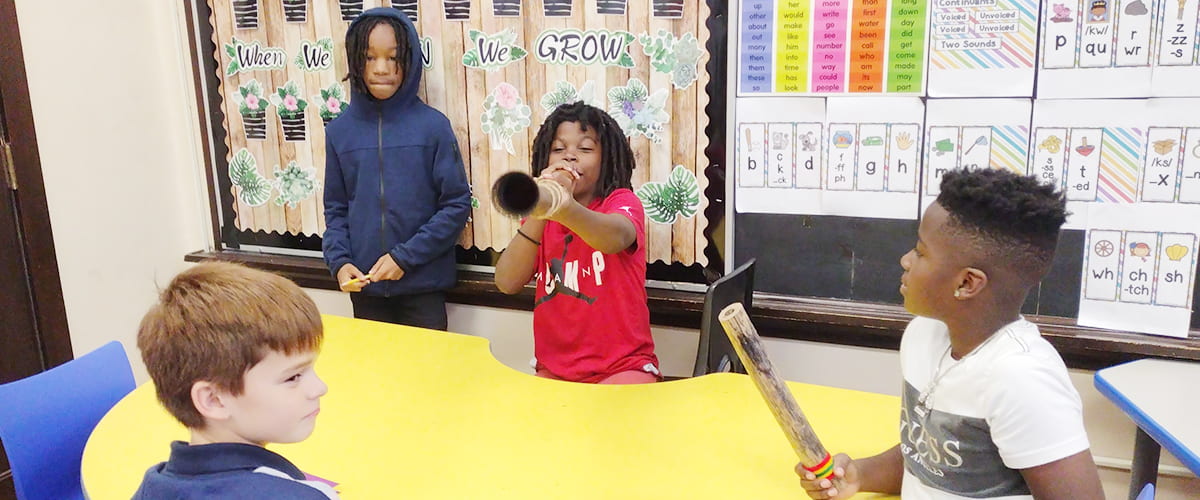

“The kids were so excited when I brought them out,” she said. “I gave each instrument to a small group and they had time to experiment with and play with it, trying to figure out how to make sound.”

Before students could do any research, they were asked to speculate on how the instruments might be used in the culture, what kind of sound waves the instrument might make, and what energy is used to produce the sound. They participated with enthusiasm and were eager to begin their research.

Using Sound Wave on Google Play, the students could see what the sound waves from their instruments actually looked like and why the various instruments produced very different looking waves. From there they dug into a set of student-generated questions: Why did this instrument emerge in its country of origin? What is the instrument used for most often in this country? Why is the instrument well suited for this use? How does this instrument generate sound?

Each group created and presented a short PowerPoint about their instruments for the class, but they were far from done learning about sound.

Most of Pyatt’s students had never been out of their neighborhoods, so a field excursion to the National Blues Museum generated a great deal of excitement. The fourth graders were impressed with the Museum’s exhibits, which bring to life the story of how songs of enslaved people raising their voices to cope with life eventually evolved into what we know as the St. Louis Blues, one of the most enduring and recognizable kinds of American music.

One exhibit explains how guitars and harmonicas became part of the music scene in St. Louis, and another, on Jug Music, challenged the students to recognize that all kinds of objects can produce sound and be shaped into music. They were invited to play instruments in a local jug band and hear recordings throughout the decades of the same three blues songs, listening for how the instrumentation changed over time.

The final step of the sound unit included participation in a contest sponsored by the St. Louis Science Museum which challenged students to develop instruments out of recycled materials. This task brought all the learning together. What could be better than a final concert with the instruments the students had created?

The students watched a short video on rhythm and beat, created their own rhythms with their instruments and performed an awesome concert for other students. They rated their performance as outstanding, and Pyatt gave their learning the same rating!

One of the things she noticed about this kind of learning is how generative it is. When students were learning about instruments from around the world, they wanted to study a map to see where these countries were located.

One of the things she noticed about this kind of learning is how generative it is. When students were learning about instruments from around the world, they wanted to study a map to see where these countries were located.

“I’ll do more with mapping next year,” she says. “Visiting the Blues Museum led to all kinds of questions about why this national museum ended up in St. Louis and what other music was used by slaves to make their lives a little easier. We could have kept this unit going all year.”

This year Meramec students are in the neighborhood, on the playground, and in the city as every grade level tries to integrate a sense of place into their inquiry. Using the community as a resource and inspiration genuinely transforms student learning…and as Pyatt discovered, the teacher is transformed, as well.

“Teaching is a lot more fun now,” she says.

**The Power of Place: Authentic Learning through Place Based Education, Tom Vander Ark, Emily Liebtag, Nate McClennen, ASCD Publication, 2020

ISP Blog Posts

valuing science learning

Feb 10 2023

addressing root causes

Feb 2 2023

It’s All About the Place

Dec 14 2022

Pride in STEM

Nov 17 2022

Challenging Narratives

Sept 21 2022

Embracing Diversity

May 24 2022

Impacting Science Learning

May 20 2022

Math Identity

April 23 2022

SLPS Principal Fellowship

Dec 12 2021

Dr. Linda Henke is the director of the Santa Fe Center for Transformational School Leadership, an organization dedicated to supporting school leaders in reinventing schooling to celebrate the best of what makes us human: our creativity, longing for connectedness, and passionate curiosity. In her work with the Center, Linda has travelled nationally and internationally coaching and consulting with school principals, superintendents and their boards.

She retired as an award-winning superintendent at Maplewood Richmond Heights, a St. Louis suburban district. Linda’s academic preparation includes a master’s degree in public relations from Iowa State University and a PhD in educational leadership from the University of Iowa. She is a certified coach through the Center for Cognitive Coaching and a trained practitioner of transformational coaching.