If the St. Louis region is to close the gap between what its workers know, and what its businesses need, it must play the long game.

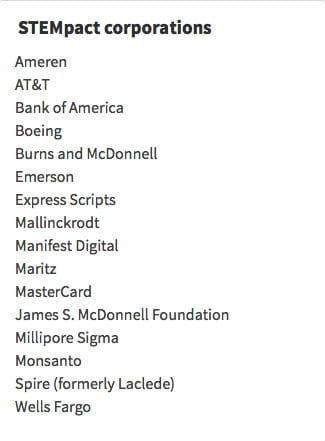

That’s why St. Louis’ leading employers, school districts and Washington University in St. Louis united to form STEMpact, an organization dedicated to improving science, technology, engineering and math education when it matters most — elementary school.

“Too many students get to high school without the confidence to tackle these subjects or an awareness of the opportunities waiting for them in STEM fields,” said Victoria May, executive director of Washington University’s Institute for School Partnership (ISP). “By then, it can be too late. Our students suffer; our economy suffers.”

STEMpact members believe the best way to develop STEM-capable students is to develop STEM-capable teachers. So in 2011, it launched the Teacher Quality Initiative Summer Program or STEM TQ, an intensive two-week seminar where teachers learn how to “stemitize” their lessons, in other words integrate STEM into all subjects from English to art, and to connect STEM curriculum to the real world, student interests and future careers.

Led by ISP educators, the program has graduated some 500 elementary and middle school teachers from almost every district in the bi-state region as well as many charter school teachers.

The immediate result: higher state test scores in math and science for the students of STEM TQ teachers. But the long-term benefit, said JoAnna Schooler of Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, will be a generation of problem-solvers poised to push St. Louis forward. The 2014 State of the St. Louis STEM Workforce finds that STEM jobs are growing fast and pay well, but that employers can’t find applicants with the right education or experience.

“STEM TQ helps close the skills gap so our young people are prepared to fill the jobs of the future,” Schooler said.

Preparing students for jobs ‘that don’t yet exist’

A beloved grade school tradition — the field trip — is a key part of STEM TQ. This summer, some teachers visited Castlewood Park, where conservationists from The Nature Conservancy demonstrated how to assess watersheds. Others traveled to MilliPore Sigma, where chemists explained how they produce life-saving drugs. Still others toured Boeing, where aerospace engineers showcased the latest in aviation technology. In all, 13 field trips took place, each one focusing on a different industry with different needs.

On one such field trip, a team of fifth- and sixth-grade teachers traveled to Ameren to discover the types of jobs that exist in the growing energy sector. Unlike many STEM TQ teachers, this group of instructors specializes in science. So they feel confident explaining to students how plant matter decomposes or gravity acts on the earth. But they didn’t know that Ameren scientists transform trash into energy, or that Ameren engineers use drones to help with line maintenance and inspections.

“The way I see it, I am preparing students for jobs that don’t yet exist,” said Eric Smith, a fifth-grade science teacher at Geggie Elementary in the Rockwood School District. “To see the range of STEM careers right here in our city is really exciting. Now that my eyes have been opened, I can open my students’ eyes.”

The teachers were especially eager to hear from a panel of four young Ameren engineers, asking about the early experiences that lead them to their careers. The engineers agreed: teachers matter.

“When a teacher loves science, students get excited too,” said panelist Emily Hart, an associate engineer. “And then there are teachers who preface their lessons with, ‘I know this is boring, but we have to do it.’ It’s so important to get students inspired.”

And don’t underestimate your students, said associate engineer Chance Alexander. He said tomorrow’s engineers need not be a math whiz, just a curious thinker.

“I was the kid who was always asking why. Why does the projector take so long to turn on? Why is our new plasma TV so much smaller than our old tube TV?” Alexander recalled. “That’s what it takes to be an engineer. The asking ‘why’ is what matters; not how you score on a math test.”

That response resonated with Jacquette Boykin, a teacher at Barack Obama Elementary School of the Normandy Schools Collaborative. Boykin is dismayed when her students, almost all of whom are low income, proclaim that they are just no good at math or science. In education-speak, they suffer from a fixed mindset. A STEM TQ course helped Boykin discover ways to help her students adopt a growth mindset — the belief that intelligence can be developed through hard work and perseverance.

“Our students don’t realize that just because they are struggling now does not mean they will struggle always,” Boykin said. “I have kids with the engineering mindset; my job is to help them get the engineering skill set.”

Making connections to the real world

Like most elementary school teachers, fourth-grade teacher Roxanne Provence got into education because she loves kids, not because she loves Newton’s laws of motion. But there she was at Pole Position Raceway trying to make a toy mousetrap car go faster. Will extra weight help? Or rubber bands fixed to the tires? She and her team spent the day experimenting with different modifications and track results.

“I am an English Language Arts person, and so this puts me out of my comfort zone,” said Provence, who teaches at Parker Road Elementary in the Ferguson-Florissant School District.

She is not alone. Many of STEM TQ’s participants said that they feel more confident teaching reading than math. And, indeed, recent research out of Stanford University shows that American teachers score below other college-educated Americans and teachers internationally in numeracy skills.

The STEM TQ initiative strives to strengthen those skills by diving deep into the concepts while offering teachers step-by-step examples of effective “stemitized” lesson plans.

“I thought this program was just going to be new strategies to teach science and math but it’s so much more than that,” Provence said. “It’s reshaped my thinking. I used to put each subject into its own category but now I see STEM is everywhere.”

It starts right here

On the program’s final day, the teachers put what they learned into action by presenting a “stemitized” lesson plan they will use to teach students this fall.

Deanna Ward, a fourth-grade teacher at Barack Obama Elementary in Normandy, transformed her water cycle unit into a multidisciplinary survey of water’s impact on human life. The lesson explored the Flint water crisis and how floods and drought shape world cultures. Her students also will be charged with engineering an irrigation system for the school garden.

Third grade teacher Cindy Ivancic “stemitized” her instruction of “Little House on the Prairie.” Ivanic told teachers that she always thought of the book as a great work of literature and fascinating exploration of American history. Now, she sees it as a celebration of science, technology, engineering and math.

“Pa and Ma had to do everything,” said Ivancic, who teaches at Discovery Ridge Elementary in the Wentzville School District. “How did they know when to plant their crops? That’s a science question. Or how to build a barn? That is an engineering question. And how did they know how much wood to cut for windows or cloth to cut for clothes? They needed to know math. All of that can be incorporated into the lesson.”

The teachers will continue to meet monthly to discuss progress. STEMpact also will track student test scores and, just as important, will evaluate whether students perceive themselves as STEM-capable learners. Prior analysis of Missouri Assessment Program scores shows STEM TQ classrooms outperform non STEM TQ classrooms in math and science by double digits.

“Our young people have a lot of opportunities in a world that wants all of them to participate,” said STEM TQ coordinator Deborah Holmes. “It starts right here with these teachers.”

School districts participating in the 2016 STEM TQ workshops are East St. Louis, Ferguson-Florissant, Hazelwood, Hillsboro, Kirkwood, Mehlville, Normandy, Pattonville, Rockwood, St. Charles, St. Louis, University City and Wentzville. Participating charter schools are Confluence Academy and Premier Charter.

The Institute for School Partnership’s collaboration with STEMpact is one way Washington University is working to improve K-12 education in the St. Louis region.

Visit The Pipeline to learn more about Washington University’s support of education in the St. Louis region.

August 2016 | by, Diane Torsion Keaggy