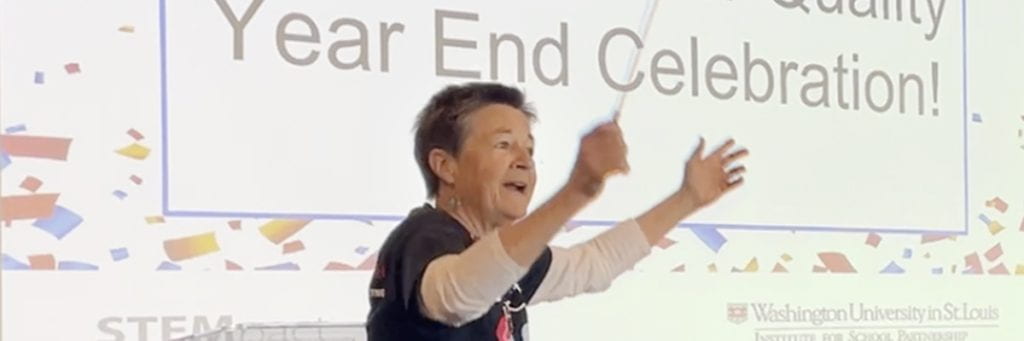

When teachers arrive for the first morning of STEM Teacher Quality (TQ) they know they’re in for something immersive and special. With support from their districts, they’ve just committed a full year of their time and energy to an experience that promises to boost their confidence and skills in the subjects of science, technology, engineering and math. They’ll get that and more.

Since 2011, more than 1,070 teachers throughout the greater St. Louis region have come away from the STEM TQ experience with fresh eyes that can see STEM learning opportunities all around them. They also see their students and themselves in a whole new way.

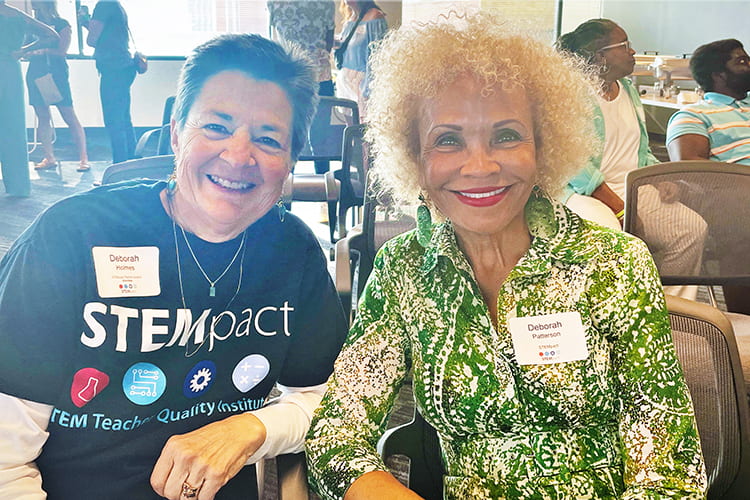

To longtime educator Deb Holmes, who was selected to co-launched and lead the program supported by STEMpact since its inception, that’s the whole point.

“We have a lot of people tell us in evaluations that they have a greater appreciation for students who have fear of STEM. They feel they are better able to support those students,” says Holmes. She firmly believes that teachers are better equipped to reach more students when they allow themselves to be vulnerable, to be curious learners, rather than holding on to an impossible standard that teachers must know everything.

“We want to help teachers be comfortable with fielding questions of curiosity for which they don’t have the answers. That’s good role-modeling,” adds Holmes. “STEMpact’s formula for success is simple and unique. We’ve identified teachers as the critical link that can increase the amount of STEM education to which our students are exposed.”

Fun field trips, new language, tough conversations

Teachers participating in each new STEM TQ Cohort kick off with a two-week Summer Institute, followed by professional development sessions that take place throughout the following academic year. Both components of the program are packed with guided learning and field trips to a number of the region’s STEM-rich locations: Castlewood State Park, the Challenger Learning Center, the Saint Louis Zoo, local raceways, Missouri Botanical Gardens and MADE Makerspace, to name a few. Additionally, STEM employers such as MilliporeSigma, MasterCard, Bayer, Ameren, AT&T, Cigna, Rankin, Victory Raceway have hosted teachers. The excursions, carefully planned by Holmes and a team of skilled facilitators, are a popular feature of the program that invites teachers to redefine themselves as STEMcapable and able to stemitize the content they’re already teaching in their classrooms. Both words are Deb Holmes originals that come to mean everything to TQ alumni.

But it’s not all fun and games.

“People would say, ‘I’m at a STEM workshop. Why are we talking about race?’ We need to support teachers who aren’t confident in STEM, but we also need to confront the historic statistics around who is defined as STEM Capable.”

Deb Holmes

“Deb Holmes knew that knowledge and confidence alone wouldn’t be sufficient to move the STEM needle for girls and students of color,” says STEMpact Founder Deborah Patterson. “She knew teachers needed help recognizing their biases and understanding how important affirmations are to improving student confidence and their outcomes in STEM. The result was a professional development program centered on equity and inclusion. At the time, there was nothing like STEM TQ in the country.”

Since the beginning, and at Holmes’ gentle insistence, TQ participants are invited to explore an open secret in the world of STEM that can make even the most well-intentioned educators uncomfortable: careers in STEM are held by comparatively few in the BIPOC community, despite a growing demand for a skilled workforce. In Missouri and Illinois, 3 out of 4 fastest growing occupations are in STEM fields, but business leaders in the region cannot find the STEM talent they need to stay competitive. The jam in the STEM pipeline, easily and historically traced to disparities in education opportunities with racial and economic fault lines, forces reckonings and strong emotions.

“People would say, ‘I’m at a STEM workshop. Why are we talking about race?’” recalls Holmes. “We need to support teachers who aren’t confident in STEM, but we also need to confront the historic statistics around who is defined as STEM Capable. It was always very much an intention of mine to address that. In those early days, the language we used centered around the achievement gap, but early on for STEM TQ, that evolved to cultural competencies. We used to get pushback from participants who didn’t think the discussions of race were relevant because their districts didn’t have black students. White students also need to see that their future workplaces will be diverse. We didn’t mince words.”

To those who have watched her navigate these courageous conversations year after year, Holmes brings a unique combination of sensibilities to each and every exchange.

Bille Mayo, a retired educator and senior consultant for Educational Equity Consultants, an organization committed to dismantling the oppression of racism in public schools, has worked closely with Holmes through STEM TQ and crosses paths intentionally on a number of other equity advocacy fronts.

“When we do this work, I’ve observed that she is careful how she couches what she says to keep audiences engaged,” says Mayo. “It’s reinforced for me that she’s able to assess a situation, think carefully about it and then couch her words in ways that encourage individuals to address their biases.”

Educational consultant Leon Sharpe, who has been a STEM TQ facilitator since the beginning, agrees.

“One of Deb’s many strengths is her ability to speak with clarity,” says Sharpe. “She centers herself as an educator with a humility that disarms most. She doesn’t come at it by lecturing. She comes at it as an ally. She acknowledges her own areas where she’s still growing. That humanizes her.”

Sharpe remembers how skillfully Holmes introduced the concept of equity to a roomful of educators.

“What she did was so fascinating,” he says. “She asked them to consider adding just one provocative word to a phrase that was commonly bandied about in education circles at the time: any child can learn. She asked them to consider an alternative: any child can learn anything. Any child can learn anything? To say that to a group of educators at the time was like throwing down the gauntlet. It flies in the faces of their training and their social conditioning. It still does. Even though tracking isn’t as popular as it once was, people do track in their minds. We form biases. Any child can learn anything is a challenge, a showstopper. People wanted to argue with her, but Deb took it a step further by reaching back to her days as an elementary teacher.”

“‘How many of you can sing?” she asked the group. ‘How many of you were told you could not sing?’” recalls Sharpe. “It’s that kind of feedback that can take the music out of the heart of a child before they can even find their voice. Then, Deb taught this group a song in three-part harmony. They hear themselves sounding good and then they get it. With that demonstration, she’s introduced a growth mindset. Maybe it’s not the person who can’t learn. Maybe, we just need to approach teaching differently.”

“I am in this now, reading books, listening to podcasts, anything I can do to know more about being part of the solution. STEM TQ has changed how I respond to students and my peers who come to the classroom with life experiences that might be totally different than mine.”

Christine Meyer

Ten years later, Holmes, Sharpe and the other TQ facilitators see that conversations about equity and education are as relevant as ever.

Christine Meyer, a K-4 PE teacher at Harris Elementary in St. Charles, was part of the 2022-2023 STEM TQ Cohort. She came in fully expecting to learn more about how to integrate STEM in her content area.

“I was pleasantly surprised with how much we learned about cultural consciousness and educational justice,” says Meyer. “I am in this now, reading books, listening to podcasts, anything I can do to know more about being part of the solution. STEM TQ has changed how I respond to students and my peers who come to the classroom with life experiences that might be totally different than mine.” Listen to what other TQ teachers have to say.

That is music to Deb Holmes’ ears. STEMpact Founder Deborah Patterson is pleased as well, remembering all that STEMpact set out to achieve with the program so laser-focused on teachers.

“Deb’s instincts to weave equity throughout STEM TQ created the best possible foundation for a program that has such potential to move the needle as we raise teacher awareness of people of color and others who are overlooked, simply not seen,” says Victoria May, executive director of the Institute for School Partnership at Washington University in St. Louis (ISP). “Our community is really fortunate to have had Deb Holmes as STEM TQ’s inaugural leader. She’s been instrumental in creating environments that re-energize teachers, help decision makers in school districts recognize the need for STEM learning and ultimately, include more learners who deserve a seat at the table.”

This year, as she passes the TQ leadership torch to Barbara Pener, another longtime TQ facilitator and seasoned STEM educator, Holmes is reflective about the strides made thus far.

“I am absolutely thrilled that we designed an experience that teachers tell us has made a difference. I would hope after ten years, that we’ve broken down more barriers,” Holmes muses, remaining hopeful about all that’s possible and still to be done.

“The world is changing very quickly. We don’t have a clue about the full, long-term impacts that Covid, gun violence, social media and remaining inequities will have on current and future generations. It’s my hope that by continuing this work, we will quit denying ourselves the talent that exists within the nontraditional demographics right here in our communities.”